General Damage by drought, or is it actually salinization?

This year’s drought will not have escaped anyone's attention, not only in the Netherlands but throughout Europe. This month we will see many of the first harvests coming in, which will make it clear how much the crops have suffered from the drought, but also from salinization. This distinction is difficult to make, because at first sight drought and salinization lead to the same type of crop damage.

Yet salinization is a different process, something we are not always aware of in the Netherlands. This is a concern, not only for researchers but also for farmers. A large proportion of the agricultural areas along the coast are at risk of salinization from rising levels of salty groundwater. Limited knowledge about this phenomenon does not always yield good policy choices. For example, 'saline crops' (i.e. highly salt-tolerant crops such as glasswort and sea lavender) may be quickly discussed as a solution for a large part of the Dutch coast. But is this really necessary, and are we really waiting for so much glasswort and sea lavender? In conversation with researchers in the field of salinization, groundwater and salt tolerance of crops, we arrive at a more nuanced picture. Read below the interview with The Salt Doctors and Acacia Water.

Figure 1. Seed potatoes August 2022 (Acacia Water)

Arjen de Vos and Bas Bruning jointly run 'The Salt Doctors' where they give advice worldwide about salt tolerance of crops and cultivation methods under saline conditions. Salinization is appearing in the news more and more frequently. This seems to me to be good for social awareness and to increase knowledge?

Yes, we are reading more and more about salinization in the newspaper. However, statements labeling salinization as 'harmful' to agriculture and nature paint an oversimplified picture. The degree to which salinization leads to damage depends on many factors, which should be the guiding principle for your farm operations and government policy.

But salinizication does lead to damage to nature and crops. Shouldn't we prevent this as much as possible?

Preventing salinization is often the best option if it is physically and economically feasible. To draw the right conclusions about this, it is important to understand various factors. First, of course, the salt concentration is important. Some crops and types of nature are so sensitive to salt that even a small increase in the salt concentration has a negative effect on plant growth. Legumes, for example, are poorly tolerant to salt, and so are natural peatlands. Sugar beets, on the other hand, were originally bred from 'beach beets'. The name says it all: this originally coastal plant can withstand salt well and, despite breeding, remains very salt tolerant. Salinization can also have negative effects on the soil itself, especially in clay soils, and this must also be taken into account.

At low salt concentrations it is also very difficult to see the difference between the effects of drought and salinization. In most cases, at a relatively low salt concentration, only the growth rate will decrease. This is because the plant needs to use energy to adapt to the higher salt concentration. As a result, the final yield will be somewhat lower. This corresponds to the consequences of drought damage. Visible salt damage, which often results in brown edges of the leaves, rarely occurs.

So it is possible to put together a crop plan with salt-tolerant crops?

Yes, if you rotate the right high-value and rest crops, it is possible. Then it is also important to consider the differences in salt tolerance between varieties within a crop. In the Netherlands, around 300 potato varieties have recently been examined closely, revealing significant differences in salt tolerance between varieties. Some of these varieties are up to three times more salt tolerant than thought. This is often not taken into account in discussions and policy decisions. This is because in the Netherlands we use old data and assume that potato is "moderately sensitive". This conclusion dates to a 1951 study based on one – unknown - potato variety in the American desert.

In our opinion, this leads to people ‘giving up’ too quickly on areas in the Netherlands that are sensitive to salinization. The discourse at the policy tables has been focused on 'saline crops' for some years now. Looking at the research results and new developments, this is going a bit too fast in our view.

Does this mean that there is a broader range of solutions than saline cultivation that is often talked about?

Absolutely, it is more nuanced than it is often made out to be. For a sustainable agricultural sector and nature conservation and development, this must be taken into account. There is a common perception that salinization leads directly to extremely high salt concentrations and that 'saline crops' grow well under such conditions. However, in many cases this is greatly exaggerated. In most cases salinization is a gradual and hydrologically complex process. Salinization in the Netherlands often leads to light or moderate salt concentrations at which specific varieties of conventional crops also grow well.

Salt tolerant varieties are therefore an option, but in the beginning you also speak of 'preventing salinization' and hydrologically complex processes, how does this work?

Saline water can enter the root zone of the plant in two ways, either through groundwater or through irrigation directly on the leaves. The first case, via groundwater, is common in agricultural areas along the coast. Salinization from groundwater is caused by salt seepage. At Acacia Water they have been researching salinization in the northern Netherlands since 2007, so they also have a lot of knowledge about solutions.

Jouke Velstra explains that if you want to keep the salt away from the roots, the 'freshwater lenses' come into play. These reserves of fresh water are located in the field, between the drainage pipes. The lenses are replenished with rainwater in the winter and in the summer the crops get their water from these reserves. If a freshwater lens is "depleted" by evaporation, the salty water reaches the plant. To prevent this, farmers can adjust their drainage so that the freshwater lenses become thicker and thus the buffer is larger. This is called 'anti-salinization drainage'.

That sounds like a good solution, but you can't see groundwater like water in a basin. How does a farmer know when his freshwater lens has run out?

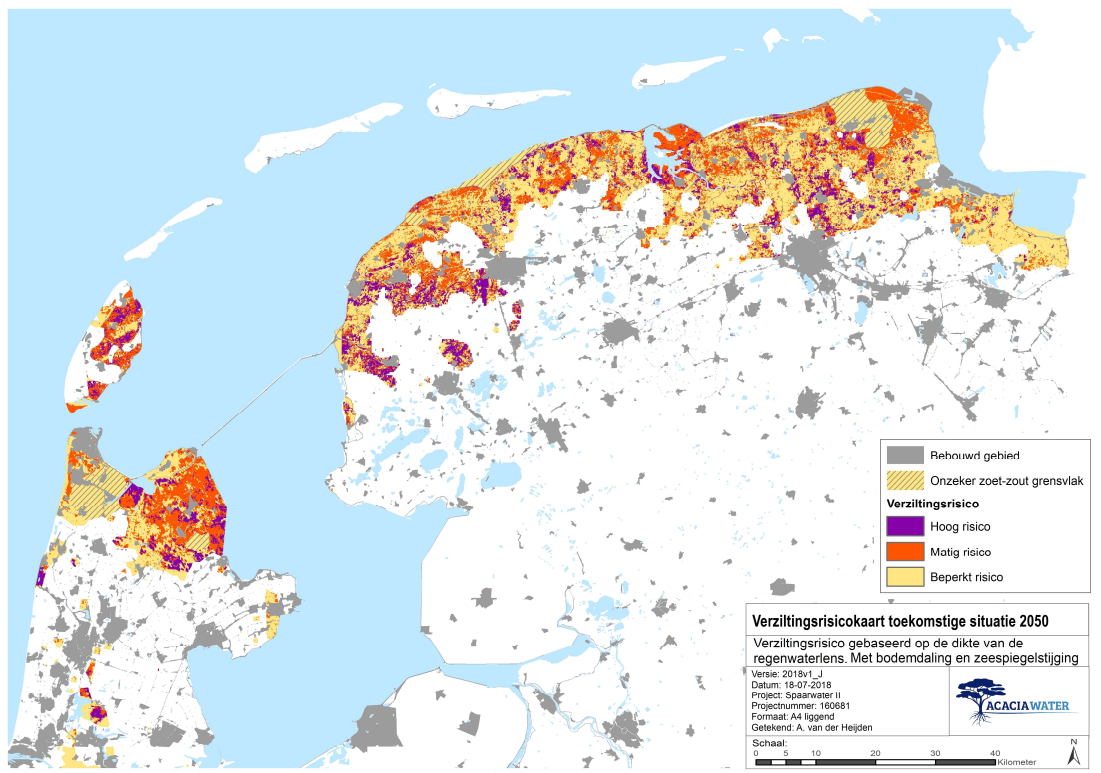

That is indeed a challenge. A farmer obviously only starts investing when there is a clear problem, and groundwater is something you can't see, let alone saline groundwater! In 2019, we at Acacia Water developed the 'salinity risk map'. This map helps to identify risk areas on a regional scale. These are also the areas where we first engage with farmers. Then they can get to work with the 'Aquapin'. This measuring instrument measures the salt content at any desired depth in the field. As a farmer, you can see from the data how thick your freshwater lenses are and what the salinity of the groundwater is. This can help with variety choices and re-draining.

Figure 2. Salinization risk in 2050 based on the thickness of the rainwater lens. The map is only suitable for use at the regional level; the risk may vary at the local scale (source: Acacia Water, 2019)

2022 was a very dry year. Did you see the freshwater lenses shrink?

We took a detailed measurement of groundwater salinity in late August at one of our experimental fields in the northern Netherlands. This indeed shows that the freshwater lenses have shrunk over the past year and the saline water has moved up. The freshwater lens has decreased by up to 30 cm in several places compared to spring 2021. Research shows that it takes longer for the lens to grow than it does to evaporate, so we need to be careful with these freshwater resources.

This understanding helps but is still not enough. It is important to get a good picture of the financial damage in order to actually make the move to new varieties or 'anti-salinization' drainage.

Future research will have to focus on these details, but that does not take away from the fact that much more is already known than sometimes emerges in the various discussions. With regard to salinization, prevention is certainly better than cure, but often the patient is less ill than people think!

Published by

Arjen de Vos

Founder & Director at The Salt Doctors

saline agriculture

saline agriculture